Mi’kmaq Architecture

The Mi’kmaq, as a distinct ethnic group, may have inhabited what they called Epekwitk, and what we now call Prince Edward Island, for several millennia. It is here that they settled and lived in birchbark shelters called wigwams.

… animate thing lying in the water ...

Photo from the internet, by WestJet pilot Steve MacDonald

Last year I came across an aerial photograph of the Island taken by WestJet pilot Steve MacDonald which had a profound effect on my perception of the Island. In this photo, I saw for the first time, an island disconnected from all evidence of French and British colonial contact. I realised at once that I was looking at a facsimile of the pre-European contact island, concealing millennia of Mi’kmaq settlement whose exploitation had been as light as a feather.

I was looking at a spiritual landscape where Nature and Life interacted seamlessly as they had for millennia.

Epekwitk is now the official Mi’kmaq name for the Island. Being a child of my times, I thought that it meant “lying parallel to the land,” or “cradled in the waves” as I had read in Rayburn (p 15). However, according to new scholarship by Dr. Stephanie Inglis called Transliteration and Morphological Analysis of Mi’kmaq PEI Place Names, it has a new, powerful, and highly evocative meaning: animate thing lying in the water.

Inglis – Mikmaq-Place-Names-Updated-5-March-2019-1

Suddenly, I became acutely aware of how little attention we have paid – aggressive colonists that we are – to how the Mi’kmaq saw their home. It was alive! It was Mother Earth!

The concept of animism completely pervaded the lives, attitudes, and beliefs of the peoples of the early First Nations. The word anima, from Latin, is used as an anthropological construct and is the only starting point our language has to describe the indigenous perception of the world and all things in it. Anima means spirit, or soul, or even life itself. Everything in the world has a spirit or a soul – the earth, water, vegetation, animals, and human beings. This spirit permeates everything in the world and infuses human activity in all its forms with a spiritual quality. It may be that their essential spiritual state was one of being at-one-ness with the world in which they lived.

It is in this animated world, in the forests, by the water, that Mi’kmaq settlements appeared on the animate thing lying in the water. As they saw it, all was alive, and they were a part of all. This is where they built their shelters, raised, and fed their families and were one with the spirit of the great world.

It is living in the wigwam that the Mi’kmaq experienced their two states of existence. The first, free to roam at will on their Island home, and the second, as marginalised, unwanted squatters on land that had been taken over by French and British colonists. These two pictures illustrate these two states.

In the late 1830s William Henry Bartlett (1809-1854) had sketched this Maritime Mi’kmaq encampment to be engraved as an illustration for the book Canadian Scenery Illustrated published in 1842. These Mi’kmaq live in the shelter of the forest, in their original dignity, at one with Nature, and not as unwelcome appendages to the British Colonial landscape.

William Henry Bartlett (1809-1854), Wigwam in the Forest, ink wash, 15.3×18.8 cm, c. 1838. NGC 6585.

Early photographs of the region show wigwams in a summer setting like these in a detail of a photo by Paul-Emile Miot. A small camp near the water defines for us the nature of such settlements on the edge of British colonial towns. A beautiful canoe has been hauled ashore and placed near the wigwam. From our point of view at this distance in time there is a powerful incongruity as the two cultures either collided or lived tolerantly side by side. These Mi’kmaq are officially homeless.

Paul-Emile Miot, detail of Mi’kmaq Women in Front of Wigwams, ca. 1857-59, near Sydney, Cape Breton. Library and Archives Canada, (PA-194632).

The Wigwam as an International Phenomenon

The wigwam appears to have a very ancient history that goes across continents. When you study the history of Neolithic Europe and even Africa, you come across excavation reports that describe finding small circular structures that were probably circles of poles arranged in conical fashion and covered with bark or skins.

The wigwam as we know it in our region seems to have been known in Classical times. The ancient Scythians, who flourished from the 7th to 3rd centuries in the Steppes of Central Asia, were nomadic people whose sole focus was the horse. They were famous all through antiquity for their exceptional horsemanship. There is archaeological evidence (Simpson, pp. 155-156) that not only did they have portable structures called yurts, but they also had structures identical to wigwams, which they covered with birch bark or animal hides, and which were also portable. This tradition survived more than two thousand years and as recently as 1926, when this photograph was taken in the Altai region, they were still in use among the nomadic peoples (Simpson p. 156).

The Wigwam in North America

Engravings illustrating the published accounts of the French missionaries in Quebec and Ontario show different shapes and sophisticated arrangements for indigenous villages in heavily populated areas. On Champlain’s 1612 map of the Maritime Region there are tantalising details that suggest a form of house that we have come to associate with the more populous Upper Canada. This particular map is interesting because it is full of anthropological and biological detail that seems closely observed, and so this kind of detail causes one to wonder if the Mi’kmaq houses represented are indeed accurate. Here is that map.

Champlain, Samuel de, 1574-1635, CARTE GEOGRAPHIQVE DE LA NOVVELLE FRANSE FAICTE PAR LE SIEVR DE CHAMPLAIN SAINT TONGOIS CAPPITAINE ORDINAIRE POUR LE ROY EN LA MARINE, 1 carte en 2 coupures, 30.6 x 17.7 inches, Bound in Les Voyages du Sieur de Champlain Xaintongeois, Capitaine ordinaire pour le Roy, en la marine. Divisez en deux livres. Ou, Journal tres-fidele des observations faites és descouvertures de la Nouvelle France. Paris :Chez Jean Berjon,1613. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ).

Here is a detail of the area around Port Royal showing probably a wolf with cabins all around him.

Could there have been houses of this kind in Acadian when Champlain was there? And to make matters even more confusing, there is a detail of what looks very much like a wigwam built by a tribe in Upper Canada.

What does it mean? We know so little about what the early colonisers saw. There is so much more research and thinking to be done.

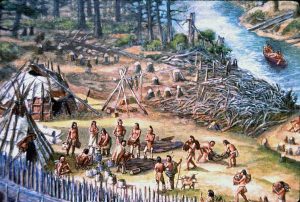

The historic illustrator Lewis Parker painted this reconstruction of a Huron village, showing the characteristic long houses, perhaps seen in Champlain, adapted to their way of life, but as well, wigwams as we know them.

http://lewisparker.ca/biography.html

The warlike Hurons and Mohawks were part of the larger Iroquois culture in Quebec and Ontario and long houses were the characteristic structures in their fortified villages. The small Mi’kmaq population of Epekwitk, always mobile, according to historical descriptions, made far less of an impact on the landscape. Although no doubt, in favourite spots to which they returned again and again there would have been clearing of the forest.

Lewis Parker, Copyright 2011

The upper left hand portion of this Parker painting portrays wigwams, that were also present everywhere at the time. This detail gives you an idea of the sort of impact Mi’kmaq settlement might have had on the environment.

The wigwam seems to have been used throughout the Mi’kmaq period, beginning in our region about 3,000 years ago. Tuck (pp. 49-51) describes the discovery by Sanger and Davis in Passamaquoddy Bay of oval house sites, wigwams, 3 x 4 metres in area that were sunken into the ground about 50 centimetres. Similar arrangements had been discovered in other places years before which led the archaeologists to believe that this was common practice in the region. Perhaps it was especially effective in winter, eliminating the draft that would seep in from wigwams sitting on the ground.

How were wigwams constructed?

The essence of the wigwam on Epekwitk was birchbark. In pre-Colonial times when the virgin forests still existed there were huge birch trees from which very large sheets of bark were easily stripped. I have in my collection a piece of birchbark that was discovered when a late Eighteenth Century house in Pownal was being re-shingled. The strip was wider but a piece about ten inches wide broke off when the bark was removed from the house. When first built the entire house had been covered with bark as insulation against drafts. There is no doubt that the use of birchbark as cladding was inspired by the Mi’kmaq wigwams seen everywhere.

Piece of birchbark house insulation, 930 x 560 cm, from a Late Eighteenth Century house in Pownal. R. Porter Collection.

In 1982 when I was studying the Nova Scotia Museum system, I came across a display where a full-size wigwam had been constructed by indigenous craftsmen using traditional techniques and a design reconstructed from old photographs. The photos that follow were taken at that time.

Wigwams were framed by arranging a conical circular structure of young trees lashed at the top with roots. A suitable space was left for an entrance and there was an open space at the top for smoke from the fire to escape. The bark was applied with the outside facing in so that a more waterproof surface was exposed. More poles were applied to the outside to support the bark from the wind.

The sheets of bark were stitched to the frame with fine roots.

An early French Missionary account of a wigwam in Malpeque in 1726.

We do not have many accounts of wigwams from people who lived in them. A French missionary left an account of life in a wigwam in Malpeque in the early days of the colony of Ile St. Jean. It is starkly descriptive, and perhaps fits well into our subsequent exploration of Mi’kmaq architecture.

In 1726 a Franciscan missionary travelled about the Island ministering to desperate Catholics in need of comfort and the sacraments. He started off at Saint Peter’s Harbour and in time made his way west. Fr. Kergariou wrote a description of his stay in Malpeque, and a transcript of it survives in MacMillan, p. 19.

” The Micmacs of Malpeque were awaiting his coming, for the missionaries never failed to pay them a visit at this season, to afford them an opportunity of approaching the sacraments during Paschal Time. His welcome here was no less sincere than that extended to him by his own countrymen, though it was, perhaps, less demonstrative owing to the reserve peculiar to the Indians. But with all their kindness, a stay in their village was one of the greatest trials that fell to the lot of the missionary. His only shelter was the rude wigwam open to all kinds of weather, and often dirty to an intolerable degree. A few spruce boughs, which served for seats by day and for beds by night, constituted their entire stock of furniture. From the fire, placed in the middle, rose a thick smoke, which, carried about by the currents of air, added greatly to their discomfort. Men, women and children were huddled together in the narrow space, while the dogs moved about at will, barking and snarling in perfect freedom, and sleeping-here and there, lying sometimes on the ground and not infrequently on the people.”

The missionary, it seems, had a nervous crisis which affected his health severely. This is a reality we generally avoid thinking about but which must have been found in all the aboriginal lands which the Catholic missionaries visited.

The 1903 Rendle Account

There is an interesting description of how wigwams were constructed on the Island in the early 1900s. For the moment I present it to you as I found it, quoted by Benjamin Bremner in his 1932 book, An Island Scrap Book. He found it in a 1903 edition of The Island Magazine in an article written by J. Edward Rendle. I will eventually obtain a copy of Rendle’s full article and add to this anything relevant that Bremner might have left out in his editing.

The Micmacs’ wigwam is a curious structure; in form and construction it differs but slightly with the homes of their original ancestors. A site is generally chosen near a stream, or shore, in a sheltered place well wooded; here the Micmac prepares his timber of construction. The frame is first raised and fastened, this he cuts out of straight spruce trees, felled and trimmed by his squaw, then he proceeds to cover it in; which he does by placing the bark of the hemlock or birch on the now upright frame, tier over tier; this he covers over with spruce boughs and lines the inside the same. Boughs are neatly spread down inside the camp forming an admirable substitute for carpets, beds, and cushions. In the winter season the door-way is also partly covered with them placed so as to spring back and forth as you pass and repass; a piece of blanket or skin hangs on the inside of the door . . . The fire occupies the centre. There sits on one side of the fire the master and mistress; and on the other the aged people. The wife has her place next the door, and by her sits her brave; you will never see her sitting above her husband; for towards the back part of the camp is up. This is the place of honor The men sit cross-legged. The women sit with their feet around to one side – one under the other. The younger children sit with their feet extended in front. Their women are acc inferiors, they maintain a respectful reserve in their word their husbands are present.

(J. Edward Rendle in P. E. I. Magazine, 1903)

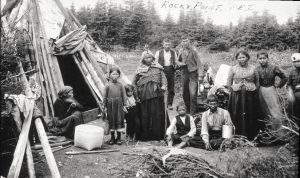

Bremner (I think its him) adds this paragraph after his quote from Rendle and I include it because of the extremely important observation that small wood stoves replaced the traditional fire in the wigwam and somehow affected the heath of those who lived in those spaces. This information is vital because it coincides exactly with the changes recorded below in the Mitchell photographs of the settlement at Rocky Point.

But coming to more recent years, conditions have changed – some not for the better. The old distinctive dress of the brave has gone, although a few donned it in my young days; but what has been claimed by many as one cause in the decline in the health of the Micmac, is the substitution of the white man’s stove for the old-time ground fire — the stove being inimical to health except as used in regularly floored houses.

How were wigwams used by the Mi’kmaq?

Various paintings by English travellers and officials from the first half of the Nineteenth Century give us an idea of what the inside of a wigwam looked like. The opening was generally made wider by the artist so that the maximum view of the inside could be included. The picture below shows what might have gone on in such a space, where a woman is working sitting next to a fire over which a pot is steaming. That must have been a very common sight. The artist is eager to show the usual things associated with the indigenous people, which were eagerly collected by British Colonial officials, and so, out of season,includes a toboggan and snowshoes prominently displayed in the summer foreground.

Anon., Canadian School, Mi’kmaq Encampment, 1830-35, Christie’s, later acquired by National Gallery of Canada.

In this painting by English artist John Toler, we have a comprehensive view of a Mi’kmaq camp on the edge of a river. Hunters returning from a fishing trip arrive and have pulled their canoe ashore. A child runs excitedly in front of the man carrying a big fish. Life goes on inside the wigwam, which is little more than a summer shelter, while men and women in the foreground talk and laugh as they sit and recline on the shore. There is an intimacy and a friendliness, probably naturally observed and not construed, that shows a happy group of unthreatened aboriginals in their environment. (At the moment I do not have a good photograph of this oil painting, only this colour plate from a book.)

John G Toler, A Micmac Camp near Halifax, oil on canvas, 13 x 17″, 1808, Public Archives of Canada.

There is a detail from another painting that shows in some detail what is going on inside a wigwam and the spill-over of domestic activity into the space outside. It is taken from an oil painting of Halifax Harbour by George Thresher done in the 1840s. The original is in the Confederation Centre Art Gallery and is displayed at Government House in Charlottetown.

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/thresher_george_godsell_8E.html

George Thresher, Halifax Harbour, oil on canvas, circa 1840. CCAGM.

This is a typical harbour scene with the exception that the entire foreground is taken up by a Mi’kmaq encampment. A canoe even braves the barrage of a nearby warship.

It was impossible to get a better image of this detail because of window reflections in the room, but a woman is clearly seen inside the wigwam working on a basket while other members of the family are outside cooking the day’s catch over an open fire. It is a very engaging scene, isolated in the lower left corner from the hustle, bustle and noise of what is going on in the harbour.

Although it dates from the beginning of the Twentieth Century this watercolour of a wigwam in Upper Canada by Edward Shrapnel give a very clear, wide-angled view of the interior, probably exaggerating the scale to create a sense of light in the dark interior.

Edward Scope Shrapnel, Family cooking in their wigwam, 1901, o.c., 35 x 55 cm. (13.8 x 21.7 in.) auction photo.

Island Wigwams

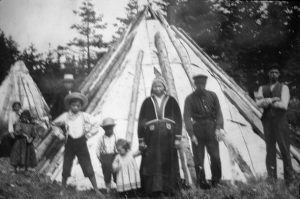

At present I don’t know if there are early representations of Island wigwams drawn at a particular place, but there are three photographs of Island Mi’kmaq which we may consider to be the earliest ever taken. It is probable that they are the work of Henry Cundall, a local entrepreneur, surveyor, and amateur photographer. The Mi’kmaq settlement nearest to Charlottetown in 1860 when these photos were taken, was just across the harbour at Rocky Point. There is still a Reservation there today. Day trips – a form of early tourism – were not uncommon as the beau monde of Charlottetown went over to look at the exotic displays that awaited them. Cundall was also surveying in Prince County in the early 1860s and had his camera with him. The photograph of the Mi’kmaw seated in front of his wigwam may have been taken on Lennox Island.

Henry Cundall (probably), Image of Mi’kmaq in front of his wigwam, at Lennox Island or Rocky Point, 1860. DuVernet Album, PEI Museum Collection at PARO.

Henry Cundall (probably), Tourists from Charlottetown photographed in front of Mi’kmaq encampment at Rocky Point, 1860. DuVernet Album, PEI Museum Collection at PARO.

Henry Cundall (probably), Mi’kmaq encampment at Rocky Point, has severe water damage, 1860. R. Porter Collection.

All these photos show the typical appearance and construction techniques of wigwams erected for all-weather occupation. They are well braced against the wind. In several photographs of wigwams large sheets of fabric can be seen as curtains hung over the openings. This most likely is canvas from sails salvaged on the beaches, washed ashore after storms or shipwrecks.

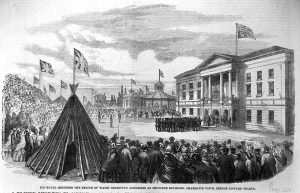

Ceremonial wigwam and members of the Mi’kmaq community at the reception of the Prince of Wales in Queen’s Square, August 10, 1860. Woodcut. Illustrated London News.

When the Prince of Wales, just a teenager, visited Charlottetown in 1860 as one of the stages of his world tour, every possible effort was made to delight him. At that time the Mi’kmaq were influential enough to get control of an entire corner of Queen’s Square to build a large ceremonial wigwam – flying the Union Jack – and to assemble a significant number of elders. The prince was pleased. For more information on that extraordinary visit read my earlier blog post at:

A PRINCELY INTERLUDE IN THE CHARLOTTETOWN TOPOGRAPHY OF 1860

Charlottetown had a local satirical poet who liked to poke fun at everything. His name was John Lepage and he turned out a couple of books called The Island Minstrel. In one of them he makes fun of the old round market house that the Prince’s entourage did not find exciting, and in these stanzas suggests that it be given to the Mi’kmaq so they could turn it into a giant wigwam where they could dance the early Eighteenth Century ballroom dance called “Hunt the Squirrel” where partners chase each other, here mimicking hunting activities. The idea was supposed to be very comical.

“Some recommend that seven fat kine at least

Be roasted whole upon the Market Square,

And to give eclat to the sumptuous feast,

That all in Lilliput alike should share,

And that for fuel dry ‘to do them brown,’

Th’ old market house be burned, that eyesore to the town.

“But others think ‘twould be a sin and shame

To burn the poor old market house, when we

Must all admit it has a righteous claim

Upon the tenure of our memory,

And that ‘twould be much better, on the ground,

To make it ornamental to the eye:

A mammoth Indian camp, all covered round

With spruce and firs, and such wild drapery

That all the Micmac subjects of our Queen

May dance a ‘hunt the squirrel’ through the sylvan scene.”

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/lepage_john_11E.html

There were many books and articles published to celebrate the presence of the handsome young prince and they are filled with fact and fiction. In this one, published by a member of the prince’s entourage, there is a small engraving in which it is possible to see the basic structure and construction of a wigwam.

Wigwam of Micmacs, engraving from Sir Gardner D. Engleheart, Journal of the progress of H. R. H. the Prince of Wales through British North America; and his visit to the United States, 10th July to 15th November 1860. Privately printed at the Chiswick Press, pp. 24-27.

As time went by and tourism in North America was invented on models that appeared in Europe in the late Seventeenth Century, various forms of art and literature were produced for this market. There were songs with engraved covers, nasty caricatures that showed the indigenous people as sub-human, and some honest photographs that show the life the Mi’kmaq had been forced into with calm accuracy.

Not only were single photographs sold, but with the advent of the stereoscope which had been invented in the 1830s, in time there developed a wild craze to walk into the picture space. These first viewers were complex, with expensive optical parts, and few could afford them. By looking through the apparatus at the same picture taken at a very slightly different angle you saw the view in startling 3-D depth. In 1861 Oliver Wendell Holmes invented a simple, very inexpensive sterescope most of us are familiar with. It consisted of two prismatic lenses and a wooden stand to hold the stereo card.

Photo Davepape – Public Domain

In 1862 the Royal Navy training ship HMS Nile visited Charlottetown and Halifax. Aboard was a Lieutenant Trotter who was a keen photographer with a sharp eye for the world around him. While in Halifax he produced several stereo pairs of a local Mi’kmaq settlement. These were for private distribution and not for sale. Here are two of them, showing life in the camp and a large group in front of a wigwam. It is full of interesting detail about the construction of the wigwam and the clothing of the Mi’kmaq.

Lieutenant Trotter, photographer, HMS Nile. Halifax 1862. Gillingwater Collection.

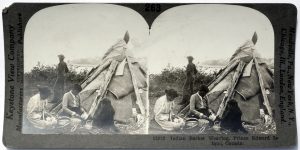

This later stereoscopic pair is more finely composed for the trade by a professional photographer.

Indian Basket Weaving, Prince Edward Island, Canada, No. 13882, Keystone View Company, Manufacturers, Publishers, stereoscopic view, late Nineteenth Century.

This rare stereoscope double photograph mounted on a printed card demonstrates the continuing touristic interest in aboriginals even at this late date. It is interesting to note that similar photographs of Afro-American families in the American south were similarly popular and for a similar reason: something exotic for white society to be amused and distracted by.

This photograph shows a low conical structure covered with enormous sheets of birchbark with the chimney hole at the top covered over with canvas to keep the interior dry in rainy weather when there is no fire. It is a typical tourist photo with women in the foreground making beautiful baskets. A man looks off into the hazy distance while houses from a nearby settlement are visible in the middle of the view.

Continuing with the popularity of tourist images, this postcard, photographed at Richmond, shows a family next to their summer shelter, scarcely a wigwam. On the left, leaning against the cedar pole fence, is a bicycle. One does not know if the fence, a British Colonial feature, is to keep them out or keep them in. European civilisation is advancing.

One of the Natives, Richmond, near Summerside, P. E. I., postcard. C. 1910.

The A. W. Mitchell Photos

There is a series of photographs taken of the Mi’kmaq at Rocky Point by the photographer Albert W. Mitchell. He was born on 12 June 1868, the son of Nathaniel and Hannah Mitchell of Charlottetown, and died on 11 April 1906. Throughout his life he worked at Prowse Brothers, a dry goods store that famously catered to the needs of the working class. He was an ardent Methodist and an important member of Odd Fellows. He is best remembered for a very significant collection of over 200 photographs and 20 glass plate negatives covering those things in Charlottetown and area that caught his fancy. He seems to have flourished between 1895 and 1906. Among his favourite subjects were the Mi’kmaq of Rocky Point. This article by Jim Hornby, and the article from the DCB, also by Hornby, tell you what is known about Mitchell.

Hornby – Mitchell – Island Magazine

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mitchell_albert_william_13E.html

This page from the Provincial Archives describes the Mitchell collection held there.

http://www.archives.pe.ca/atom/index.php/w-mitchell-fonds-2

Among Mitchell’s photographs are larger views of the Reservation that give us an idea of the spatial relationships between the family wigwams.

Contact print from glass negative – R. Porter Collection, private printing.

Mitchell was also interested in showing individuals, just standing before their wigwams, or seated on the ground working on their baskets for which there was a large market. This is visible in this series of photographs that could be used to cater to the tourism market. They could easily be turned into postcards.

Barbara Morgan proof, Mitchell Collection, PEI Heritage Foundation.

Barbara Morgan proof, Mitchell Collection, PEI Heritage Foundation.

Barbara Morgan proof, Mitchell Collection, PEI Heritage Foundation.

Barbara Morgan proof, Mitchell Collection, PEI Heritage Foundation.

This dignified matriarch in front of her home has always appealed to viewers and was even produced as a very popular postcard to sell to tourists.

Barbara Morgan proof, Mitchell Collection, PEI Heritage Foundation.

Look at her large “Phrygian” headdress with all its elaborate embroidery and bead work! That is all that was left of her ancient culture. It was full of symbolism cursed by the Christian church and was perhaps a defiant gesture to tell the world that the old ways of the Spirit of the World were not lost.

A major design change in the Rocky Point Wigwam

By now you will have noticed that at Rocky Point the wigwam is no longer conical but pyramidal. This is a very significant moment in Mi’kmaq history when the efforts of missionaries, Catholic and Baptist, to destroy the Mi’kmaq culture and civilisation through the process of conversion was reaching its height. Conversion to Christianity ultimately required the Mi’kmaq to abandon their ancient ways to imitate the white Christians who lived in traditional houses that were square or rectangular and who wore clothing, not embroidered robes and suchlike. Increasingly the Mi’kmaq are dressing like their white overlords and their wigwams, the pride of millennia, are now something to be ashamed of. To please God, they had to adopt white ways. Therein lay Salvation.

Barbara Morgan proof, Mitchell Collection, PEI Heritage Foundation.

An Ominous Portent

The first sign that I have been able to discover that, apart from the conversion of the wigwam cone into a square pyramidal shape, colonial frame architecture has finally intruded into this very ancient form is this photograph, a screen capture from the film, Spirit World: The Story of the Mi’Kmaq, available on YouTube and largely produced by Prince Edward Island Mi’kmaq and deeply committed Islanders. It comes as a violent shock to see a Mi’kmaq woman emerging from a frame house door clumsily inserted in the side of the wigwam. Gone for good is the traditional curtain of hide.

Screen capture from the film by Pollard and others, Spirit World: The Story of the Mi’Kmaq, distributed by YouTube.

Primary source: Miot collection. National Archives of Canada file #C75915.

Returning to the Mitchell photos – the most important of all, I think – this one tells all. The Mi’kmaq were being assimilated and were prepared to abandon their traditional home, thousands of years old, to live in structures that related directly to the British settlers of the Island.

This little house captures a disastrous moment in the assimilation of the Mi’kmaq. It is only as tall as a wigwam because that is all the vertical space their actual needs require them to have. However now the circle (or square) of poles is abandoned and has been replaced by a braced frame construction, just the way the houses of the colonial population of the Island were built. It is raised off the ground on sills, has a door and windows flanking it. It is almost a parody of a Georgian central plan cottage. In haste, it is clad with whatever materials are at hand. The family sits in front of it. Are they happy at the momentous architectural change they have wrought that, at one stroke, has destroyed millennia of the traditional wigwam?

I find this photograph deeply distressing and depressing as it celebrates the death of tradition and cultural continuity, and a readiness to adopt the domestic ways of their Christian mentors and controllers.

Contact print from a Mitchell glass negative, Heritage Foundation – R. Porter Collection, private printing.

The earliest wishes of the missionaries and administrators that the Mi’kmaq adopt European ways and become “civilised” were coming true. The Mi’kmaq will rush in droves to live in Western frame houses, and new memories will be formed, obliterating the richness and truth of their past.

Lennox Island in 1880 – Meacham’s Surveyor documents the progress of architectural reform.

Meacham in 1880 produced a very fine and exact map of Lennox Island and reproduced it in large format in the ATLAS.

What is astonishing – and wonderful – is that the surveyor, Clement Allen was so sensitive to the landscape that he carefully distinguished between houses and wigwams when he drew this portion of the settlement. You can see the icons for houses and wigwams quite clearly.

This vignette is packed with information, from the topography of the island with its frequent bogs, the road of access then beginning at the Catholic Church, and the main street going east on which are located the residences of those landowners who live in houses or wigwams.

This progress was observed not only by Allen the surveyor but also by Islanders, especially this Summerside journalist who was overreachingly eager to describe the rate and details of absorption into white Christian society. Patronised beyond endurance, their self-respect was being systematically destroyed by the process of Christian assimilation.

More Evidence of the Rise of Civilisation among the Mi’kmaq as described by the Summerside Journal.

In the Summerside Journal of 1 August 1899 an unknown reporter who signed as “Com” wrote this very glowing and informative article on the state of affairs on Lennox Island, documenting the MicMacs steady rise to Civilisation. I am grateful to Georges Arsenault for bringing this to my attention several years ago. It perfectly illustrates the architectural intention of the photos above that the aboriginals should allow wigwams to become a memory and move into Western spaces. After all, it was a major step on the road to civilisation and ultimately, Salvation.

Although a bit long, I think that this article is important enough to warrant its complete inclusion. Assimilation is well on its way:

This secluded spot forms one of the most charming of the many isles that surround our island home. Here the poor Micmac, when forced to withdraw from his then quiet retreat on the mainland, was obliged to seek refuge, and here, in his own peculiar way, shut out from the busy world around him, he still lives and seems to find life as enjoyable as many who consider themselves in a higher and more promising position. It is very wonderful, too, the improvement he has made in the quiet little home which God has given him. I know it is a prevailing opinion among us that the Micmac does not always avail himself of the opportunity of earning his own living. Though this may be true in some cases, it is almost impossible for any person to visit the island at this season and not be obliged to think differently. Considering the natural propensities of the Micmac, and the perhaps rather isolated position in which he is placed (apart from and above all aid received from Government) I think in the same length of time he has made as much progress on his island as the white man has on the one which he considers the gem of the North Temperate Zone. I do not say the same progress, but I do say the same in proportion to circumstances.

Thirty years ago, with the exception of one or two patches, the wild forest here reigned supreme. All Lennox Island could boast of were two houses. The rest of the tribe lived in camps made from the bark of the white birch, but many a change has taken place since then. Now the clear field and the cultivated farm everywhere meet the eye, and every farmer has his own house and barn. There are on the island at present over thirty houses, and only one camp. Four new houses are in course of erection, under the superintendence of M. P. Francis, who is generally thought to be the best carpenter on the island. All the farms are nicely fenced with spruce poles, which are found on the respective farms. There is, too, a very neat little church, which is kept in a very fashionable style, and the church grounds are enclosed by a substantial board fence.

One of the most enterprising farmers is Mr. John Copage, who, when visited, was busy cutting his hay, which consisted of timothy and clover in such a heavy crop that it was far better than most of the P.E.I. farmers could think of, and all that the best of them could desire. Mr. Copage has fifteen acres of land and has sown this year thirty bushels of oats, two of wheat, and six of potatoes. He has also a very nice orchard to which he has added one dozen imported apple trees and one dozen currant trees. He has also a nice house and barn, two horses, spring tooth harrow, jaunting sleigh and robe, and many other of the necessary farming implements.

The next farmer visited was Mr. P. G. Francis, who is married to Maria Blacquier of Egmont Bay. The result of this union is two half-breeds, which Mr. Francis says (and I think all agree) are well worthy of admiration. His farm is about the oldest on the island, being in part the old homestead of the Francis family, and containing sixty-three acres. Crop sown this year consists of the following: four bushels of oats, two of wheat, eight of potatoes, and a quarter of an acre of turnips. He has a very fine orchard for which he has imported a number of apple and currant trees. He has a very nice house and barn, five head of cattle, three sheep, and a number of fowls. Mr. Francis is only a beginner, and being a very industrious man, of a kind and genial disposition, is sure to succeed.

The next farmer of importance is Mr. Joseph Francis, the chief of the Micmacs, who also does a good business at fishing. His crop this year, though not so good as last, has a very promising appearance. His wheat is extra good, some parts of the field having an average height of four feet. The potato crop, too, is good. He planted twelve bushels. There is also an orchard on the farm with imported apple and currant trees. Mr. Francis has two cattle and a number of fowls, and is in a fair way of reaching the position of a good farmer.

The farm adjoining is owned by Peter Francis, whose crop this year consists of wheat, some of which measures four feet, potatoes, and a very neat little garden. He has also a large fat ox, which would likely be a prey to some of our butchers, could they make it convenient to see him.

Next comes that very popular man, Peter Mitchell, who never neglects visiting his white friends. Peter too has a good crop and seems to feel very thankful for it. It includes oats, wheat, potatoes, a fine field of upland hay, and an orchard with imported trees. His garden is extra fine, some of the pea stalks measuring seven feet in height.

The next worthy of mention is Thomas Thomas, whose crop comprises oats, wheat and potatoes. His place looks very well. He has one horse, two cattle, and a nice house and barn. There are many others worthy of mention, but my report has already reached sufficient length.

There is something else though that I must refer to. I think the visiting of the Island by the Superintendent, Mr. Arsenault, is done in a very partial manner. I find that last year only those who are well off and have no need of any support were visited, while the very poor ones were entirely neglected. One house I visited containing two families was in a very dilapidated condition indeed. The husbands had gone away drinking, one of whom had (the women said), been arrested by the Summerside police for misbehavior. These families were in almost a starving situation, and both of the women having large families were unable to go out to get anything to eat. I don’t say the husbands should receive any aid, but do think that these poor creatures not in the blame should receive some help, or be attended to in a better way than at present. – Com.

What can one say?

The Cummins Map and 1920s Progress

In 1928 a second atlas of Prince Edward Island was published by the Cummins Map Company in Toronto. It too provided a very fine map of Lennox Island showing all the developments that had taken place since Meacham’s ATLAS of 1880.

Atlas of Province of Prince Edward Island Canada and the World, P.E.I. Atlas 140 pp., World Atlas lxxii pp., Published by Cummins Map Co., M. S. Arniel, Manager, 70 Lombard Street, Toronto, Ont., Copyrighted [1928].

Cummins gives no clues on the map whether anybody is still living in a wigwam, although it is possible to assume that a few members of the community might have done so. What Cummins does, which gives to Lennox Island a degree of dignity in the larger scale of Island population statistics and provides proof of the success of the assimilation progress is this rural directory for the reservation.

But were the Mi’kmaq really assimilated? And were they fully functional members of the Island population. The answer is a resounding no! Following practices in other parts of Canada the Mi’kmaq were to be kept apart from the general population in government-controlled reservations. There, they would be administered internally by a Chief and Council. The presence of the Catholic Church, and Protestant missionaries, assured Islanders that the process of destroying every vestige of ancient religion and culture was in good hands and in full swing. The language was encouraged to languish and die because what use was it in the new society of which they were now a part, even if it was a segregated one. The first European language the Mi’kmaq had learned was French from the missionaries who came early in the Nineteenth Century. Language confusion followed after the British conquest of 1758. I discuss this process and the people involved in my earlier blog post at this link.

EARLY EXPLORERS AND THE BRINGING OF CHRISTIANITY TO THE MI’KMAQ

The Turn-of-the-Century Image

Segregation and assimilation – a contradictory concept! – did not bring the Mi’kmaq much comfort. Even God who, having perhaps entered their souls, could do little to improve their lot. There is even a reference in the records of the Prince Edward Island Legislature (I have yet to re-locate this passage) that declares cheerfully that one should not worry because they were dying at such a rate from disease and drink that soon they would all be dead.

Nevertheless, fascination with the Mi’kmaq, from a touristic point of view, increased and at the turn of the century some quite lovely postcards were published, such as this 1905 coloured card published by the Summerside Journal, showing the Provincial Arms and a Mi’kmac woman wearing her very beautiful beaded traditional hat, taken out of the architectural context of Rocky Point. This is a positive view, not caricature, and there is dignity, even majesty, in the pose of the subject.

Courtesy Phil Culhane Collection

The Music Hall Caricature

Music Halls, especially in the United States, but with long fingers that reached quickly into Canada (popular music travels very fast) gloried in songs and dances that featured the Negros and the Indians. Here is a lithograph from the title page of a music hall song about “Lo the poor Indian,” shown as a grotesque drunk emptying a bottle of liquor and in the inscription below, taking the blame for inducing white men to drink.

Vance, Fred T., Vance, Parsloe and Company, NY City, lithograph, 9 in x 7 in, Library of Congress Harry T. Peters “America on Stone” Lithography Collection, Acc. 228146, 1875.

There were several such songs that appear from the 1840s onwards, all ultimately being inspired by the words, very well known, of the English poet Alexander Pope (1688-1744) who at the beginning of his Essay on Man mused upon the condition of North American aboriginals:

Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutor’d mind

Sees God in clouds, or hears him in the wind;

His soul proud Science never taught to stray

Far as the solar walk or milky way;

Yet simple nature to his hope has giv’n,

Behind the cloud-topt hill, an humbler Heav’n,

Some safer world in depth of woods embraced,

Some happier island in the wat’ry waste,

Where slaves once more their native land behold,

No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold.

To be, contents his natural desire;

He asks no Angel’s wing, no Seraph’s fire;

But thinks, admitted to that equal sky,

His faithful dog shall bear him company.

The songs that followed, originating in American Music Halls, pick up on this image from the European Enlightenment and go on to tell a sad story of loss and decay.

These songs came to Canada, and into my life, in a very small-town, intimate way. My grandfather, as many young men of his generation did, left the Island during the idle months of winter when there was no fishing, and went to work in the lumber camps of Maine and New Brunswick. Most amazingly, Gerard LeClair from Tignish, whose father had been my grandfather’s great friend in the early days of the century, produced a photo of a Maine lumber camp which shows my grandfather – he was a big man – on the left, with his beloved pipe.

Lumber camp photo courtesy of Gerard LeClair.

My grandfather brought home this song in those years and was still singing it when I was a boy around 1950. This version from an Island newspaper I found on the internet (no date), is very similar to what I heard at that time.

Mi’kmaq as Wanderers

As far as we know the Mi’kmaq wandered across the Island seasonally from one favourite place to another. There may not have been fixed, long-term villages. Certainly their houses – the wigwam – could not have been of much use beyond a season. The beautiful baskets they made, along with other containers, had been popular in the Maritime region, and also in Quebec, since the Eighteenth Century. There are many stories, mostly undocumented, of Mi’kmaq travelling across the Island, living in temporary camps, and selling their wares at sites in towns and villages. They were a favourite subject for artists and in an earlier post I reproduced paintings of Mi’kmaq going into town and, in Charlottetown, selling their beautiful wares on the steps of what then served as the fire station. All of us who grew up during and after World War II can recall seeing Mi’kmaq on the roads, their backs loaded high with baskets, visiting one house after another. My grandparents had a supply of them, beautifully dyed for use in the house and tough, heavy baskets for potatoes. Historian Georges Arsenault in his folkloric work collected this wonderful anecdote which he passed on to me in a personal communication (2022-02-02):

Il semble que les Mi’kmaq ont continué pendant les premières années du 20e siècle à se construire des wigwams lorsque l’été ils sortaient des réserves pour aller plus ou moins camper là où ils trouvaient les ressources pour faire des paniers et autres choses. Je sais qu’ils allaient notamment à Wellington et à Mont-Carmel. La vieille Madeleine à Lamand Richard (1880-1974) de Mont-Carmel racontait dans une interview que pendant sa jeunesse des Indiens campaient l’été dans le bois pas loin de chez elle. Elle les avait suffisamment fréquentés pour apprendre une de leurs chansons.

It appears that during the early years of the Twentieth Century the Mi’kmaq constructed wigwams when, in the summer, they left the reserves to go camping in places where materials to make baskets and other objects were available. I know that in particular they went to Wellington and Mont-Carmel. The elderly Madeleine à Lamand Richard (1880-1974) from Mont-Carmel told me in an interview that during her youth some Mi’kmaq camped for the summer in the woods near her home. She spent sufficient time with them to learn one of their songs.

What a delightful story, with the young Madeleine Richard actually spending enough time at the local encampment to learn a Mi’kmaq song! How wonderful it would be to know more of these stories which help to counteract the the negative image spread around by music halls and politicians.

Georges very kindly pointed out this passage from the Wellington Senior Citizens’ History Committee’s community history, By the Old Mill Stream: History of Wellington 1833-1983, which gives insights into turn-of-the-century Mi’kmaq architecture and lovely details of their way of life among the Acadian community of Wellington. Remember that the Acadians and Mi’kmaq had been on friendly terms for a couple of hundred years. Here is the passage:

The Micmac Indians were regular visitors to the Wellington area prior to the arrival of the white settlers. It is unlikely that they stayed longer than a few months on each visit. In earlier times, the Micmacs camped during the summer along the beaches of Prince Edward Island’s north shore where many varieties of fish, shellfish, roots and berries were readily available. When summer ended they left the beaches and the cold north wind and moved inland along the rivers where they found shelter and game.

Older residents of Wellington recall that around 1900 there were 25 to 30 Indian camps near the Village, most of them along a small brook called Indian Brook which crosses the Mill Road and C.N. tracks and empties into the Ellis River at a point opposite the present day sewage lagoon. Deep springs provided them with plentiful water, even in the coldest months of the winter.

Families lived in [wigwams], making ax handles, baskets, wash tubs and butter tubs from ash and maple found nearby. The ash was split into long strips, dyed with different colors and woven into very attractive baskets of many shapes and sizes. These items were sold in Wellington and neighbouring communities or traded for flour and other staples.

These early encampments were often visited by the white people and relations between settlers and Indians were very friendly. The Indians were said to be good-natured and enjoyed dancing and playing the fiddle. Their children sometimes attended the local school. Many recipes for making medicine from berries, twigs, bark and roots were passed on by the Indians, while in later years, it was they who called upon white doctors and midwives to aid in sickness and childbirth.

Residents recall changes which occurred in the Indians’ lifestyle after 1900, particularly in the way they constructed their shelters. In the winter encampments, tar paper replaced birch bark as the outer covering of the teepee. After 1920 Indians wintered here in tarpaper covered wood frame shacks often no larger than 10 feet by 12 feet. These contained a stove but very little furniture and an account of a childbirth related by Dr. Raymond Reid describes sleeping quarters which consisted only of spruce boughs covered with blankets.

Elizabeth Perry Brown’s recollections (1977).

There is another fascinating story told about Mi’kmaq wanderings in Prince County and the exact nature of their interaction with the local people. Once again the resourceful Georges Arsenault has provided me with an account, rich in detail, found in a booklet printed by Elizabeth Perry Brown in 1977 in which she recalls the annual visit to her home of a Mi’kmaq family out to trade baskets for food with the local people. Her description is very clear, very specific and illuminates in a specific and general way what must have been many such encounters in the first half of the Twentieth Century.

When on a spring morning a slender spiral of blue smoke appeared above the fringe of trees and bushes bordering our river, it meant one thing–the Indians had come on their annual trip up river.

…

Each spring a family came up stream during the night, set up a tepee or two and that’s where the smoke came from.

We kids were not afraid of them but we did not play on their side of the water during their occupation. However, we were enchanted and wondered how soon they would come to call. They did, usually during the forenoon following their arrival.

There were about six of them. One man, his wife, we supposed, and about four girls of various sizes. We got to recognize them as the same family who came each year.

The man stayed outside as a rule, talking to father. Anyway, I don’t ever remember him inside the house. Later, father would tell us how sternly he spoke to the Indian, calling him a heathen, as at some time or another father learned that none of them attended church. In retrospect I wonder what would have happened had they, some Sunday, in a group, arrived at St. Anthony’s.

While the Indian and father discussed religion and other things outdoors, the women entered and sat in a semicircle on the chairs which we kids had arranged in the kitchen. There was very little conversation among us females–“good day”, “fine day”, “tea”, “ya” and mother busied herself – strong tea, rich milk, many spoonsful of sugar in each cup; no conversation. As I remember, they were quite attractive people and we kids stood around and stared at them.

Their visits were not wholly social; probably not social at all as each person carried at least four baskets of various sizes and designs. They were so beautiful and smelled so good! There were bushel and peck sizes. Then several smaller sizes. Pretty!

As I remember, the bartering which ensued was interesting. Mother would pick up a basket and say “one hen?”, “no”, “two hens?”, “ya”.

Another basket — “butter?”, “milk?”, “potatoes?”, “lard?”, “turnip?”, “flour?”, “eggs?” –on and on —. Eventually mother had the baskets she wanted, the squaws had the food they wanted; father also had dickered for the larger baskets — likely with tobacco.

Everyone was happy — smiles all around.

Two or three days later — no smoke.

Indians go

The story of the Mi’kmaq and their wigwams in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century, and their relationsgip with the Acadian and English community, is yet to be told. It is from sources as these that a beginning to that sad – and happy – story will be found.

A Church for Lennox Island

Lennox Island, the traditional and most visible focus of the Mi’kmaq presence on the Island continued to develop. Since the Nineteenth Century it has had a beautiful large Catholic Church, the Mission of Saint Anne, which was first established in 1801. In 1895 George E. Baker who also designed the church at Miscouche, designed this fine Gothic Revival for Lennox Island. The feast day of Saint Anne, the Mother of Mary is July 26 and for generations has been the occasion for religious and festive activities on the island, drawing many visitors.

Mi’kmaq progress in the late Twentieth Century

By the late 20th Century there were four Mi’kmaq Reservations on the island. The major one was on Lennox Island, called the First Nation Reserve, and the Abegweit First Nation had branch reservations at Scotchfort, Morell and Rocky Point. In these disparate and constricted locations, the Mi’kmaq operated within their own political system, funded by the Government of Canada and with liaison with the province of Prince Edward Island.

As the later Twentieth Century progressed the Mi’kmaq, largely on their own initiative, tried to make their presence and their ancient history known through a variety of means. The most visible of these projects was the construction of a model Mi’kmaq village at Rocky Point based on life in pre-contact times. There was a generous selection of displays showing, with life-size models, what was remembered from the previous centuries.

Postcard from the Rocky Point Micmac Village, circa 1970s.

I visited this outdoor museum at Rocky Point in the mid-1960s. The Mi’kmaq knew exactly what story they wanted to tell visitors. I do not have any information on the length of time this project existed but will insert it when I find it. During its period of operation a number of coloured postcards of the exhibits were produced and have now become collectors’ items.

PROPOSAL FOR A MI’KMAQ MUSEUM AT LENNOX ISLAND

As the Twentieth Century came to a close, and as a large number of Community Museums on the Island had upgraded their organisation and displays, it was felt by the Lennox Island Band Council that there should be an historical museum on Lennox Island. In my capacity as Heritage Consultant I was hired to write a preliminary planning study that would present an outline storyline that could be used as the basis for future discussions that might lead to the construction of a museum. Using the spelling preferred by Chief Sark I presented 20 copies of my study in 1998.

Somehow it was easier at that time to come up with an outline of a possible story line that would be considered relevant. Today such a proposal would have to be adjusted to the many changes there have been in Mi’kmaq self-awareness and development, and aside from interpreting the remote past, the narrative would lead directly into the accomplishments of the present and the dreams for the future.

A change in national attitudes

The Federal Government established a new national Day of Reconciliation that was also a public holiday to help the nation, in its great diversity, become aware of what assimilation had done from earliest historical times to destroy the indigenous cultures and their religions. Connected to this sadness was the massive grief experienced when hundreds of unmarked graves of children who had died while attending residential schools were found and excavated. This new public holiday, coupled with historical information about atrocities in general, and in particular, will in time, change national attitudes.

The Mi’kmaq today.

For a long time there had been an urgent need for a building in Charlottetown that would symbolise the process of reconciliation of past injustices and thoughtless practices that had sought to destroy indigenous history, religion and culture. There was also an urgent need on the Island for the two first nations with leadership at Lennox Island and Morell to have facilities to meet, share the essence of their common culture and plan together for the future. To that end the Epekwitk Assembly of Councils Building was built on Water Street with a glass tower that overlooks the city where, a long time ago, politicians hoped the Mi’kmaq presence would go away forever.

In a CBC interview Drew Bernard, the 23-year-old assistant site supervisor for the project, and a member of Lennox Island First Nation, proudly showing the stunning panoramic views of Charlottetown from large windows in the curved room told reporters, “This room is the Epekwitk Assembly of Councils room, where both of the bands will be coming together to discuss matters that affect all Indigenous people on the Island.”

Although there are many boggy areas on the island development continues in a variety of ways as new facilities are developed and new homes are built by the Mi’kmaq. As well as a school the Lennox Island has a cultural centre located in the former parochial house.

Satellite view of Lennox Island – Google maps 2021

Alive and well – a fascinating homebuilding project.

In my last post I told you how I came into contact with Ben MacLeod of Northam and how he introduced me to a project his company, JBM Earthworks of Tyne Valley, had been contracted to construct on Lennox Island. In a forest, on the side of the road, a clearing which respected the sacred nature of the woods had to be prepared in which to place a portable home. This client wanted to return to the edge of the forest, and in a clearing, live with ancestral spirits all about. Ben provided me with photographs and details of the story of the project and I am very grateful.

The first photograph shows the heavy equipment removing those parts of the forest where the home and its surrounding space was to be placed. It all looks very threatening. The contractors however used their judgment in leaving small clumps of trees that would help articulate the space once the project was done and the site began to mature.

Photo courtesy of Ben MacLeod

A most interesting coincidence occured while JBM Earthworks were clearing the forest site for this project. Google Maps took new satellite photos at that very time and even the excavator and other equipment are visible in this detail. The decision to build in the forest was immortalised.

Here is the site after the rough landscaping had been completed and the house, an austere mobile home, had been hauled with difficulty into place among the carefully preserved clusters of trees. A few clusters had to be sacrificed. Even in this early state of development the site is full of exciting promise and is like an old landscape painting showing a country house in its natural setting.

Photo courtesy of Ben MacLeod

My desire in this blog post was to emphasise CONTINUITY of form, function and inspiration. Although the wigwam is now only seen in museum reconstructions and at Mi’kmaq festivals and celebrations, the idea of the house in the woods is alive and well, and even today, can be admired on Lennox Island.

THANKS

Several years ago Georges Arsenault brought to my attention this deeply interesting article from the Summerside Journal of 1 August 1899 which I have included in my text. I am grateful to him for his thoughtfulness. Georges also very kindly pointed out inaccuracies in my text and provided me with a couple of very poignant anecdotes which I have included in this essay. Thank you Georges.

Ben MacLeod made photos available to me and described clearly his role in the preparation of a site in the woods for the placement of a portable home for a Mi’kmaq client. For this I am very grateful.

More recently (July 30, 2023) Brian Pollard provided me with a link to his film, Spirit World: The Story of the Mi’Kmaq, available on YouTube, and identified the National Archives reference for a most particular photo. Photograph Primary source: Miot collection, National Archives of Canada file #C75915. Thank you Brian.

REFERENCES

Augustine, P. J., The Significance of Place in Textual and Graphical Representation: The Mi’kmaq on Lennox Island, Prince Edward Island, and the Penobscot on Indian Island, Maine. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Arts, in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Charlottetown, PE, 2010. Retrieved from: https://islandscholar.ca/islandora/object/ir:21763/datastream/PDF/download/citation.pdf

Betts, Matthew B., & Hrynick, Gabriel, The Archaeology of the Atlantic Northeast, University of Toronto Press, Toronto, 2021.

Brown, Elizabeth Perry (1902-1980), The Way Things Were, privately mimeographed, 1977.

Denys, Nicolas, Concerning the ways of the Indians: Their Customs, Dress, Methods of Hunting and Fishing and their Amusements [1672], The Nova Scotia Museum, Halifax, 1979.

http://www.parl.ns.ca/nicolasdenys/index.htm

Engleheart, [Sir] Gardner D., Journal of the progress of H. R. H. the Prince of Wales through British North America; and his visit to the United States, 10th July to 15th November, 1860. Privately printed at the Chiswick Press, pp. 24-27.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbtn.43560

Hoffman, Bernard Gilbert, The Historical Ethnography of the Micmac of the Sixteenth And Seventeenth Centuries, PhD Thesis, University of California, 1955. PDF of typescript from the Library of Indian and Northern Affairs, Canada. Scanned June 2012.

Hornby, Jim, “A. W. Mitchell, Photographer,” The Island Magazine, No. 12 Fall/Winter 1982.

Hornby – Mitchell – Island Magazine

MacDonald, Edward & Joshua MacFadyen & Irene Novaczek, editors, Time and a Place: An Environmental History of Prince Edward Island, McGill Queen’s University Press and Island Studies Press at UPEI, Montreal and Charlottetown, 2016.

MacMillan, Rev. John C., The Early History of the Catholic Church in Prince Edward Island, Evenement Printing Co., Quebec, 1905.

Pollard, Brian, and others, Spirit World: The Story of the Mi’Kmaq, film, film, 1:04 minutes, YouTube. Photograph Primary source: Miot collection, National Archives of Canada file #C75915.

Rayburn, Alan, Geographical Names of Prince Edward Island, Surveys and Mapping Branch, Department of Energy, Mines and Resources, Ottawa, 1973.

Sark, Tiffany, “Mi’kmaq Baskets: Our Living Legends,” pp. 9-24 in First Hand: Arts, Crafts, And Culture Created By PEI Women Of The 20th Century, PDF edition for Women’s History Month 2017 unupdated & uncorrected. Originally published in 2000 at www.gov.pe.ca/firsthand and as a CD-ROM. Created by The PEI Advisory Council on the Status of Women and the PEI Interministerial Women’s Secretariat.

Simpson, St. John, Scythians, Warriors of Ancient Siberia, British Museum catalogue, Thames and Hudson, 2017.

Summerside Journal of 1 August 1899.

Tuck, James A., Maritime Provinces Prehistory, Canadian Museum of Civilization, 1995.

Wellington Senior Citizens’ History Committee, By the Old Mill Stream. History of Wellington 1833-1983, published by the Senior Citizens’ History Committee, Printed by Williams and Crue (1982) Limited, Summerside, 1983. pp. 4-5.